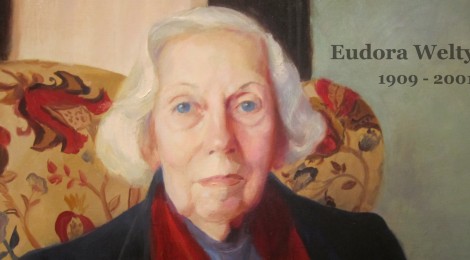

Nothing is Ever Really Lost: Time and Memory in Eudora Welty’s “Music From Spain”

Eudora Welty’s life and work share a fascination with memory and time. “Of course the greatest confluence of all,” Welty writes in her memoir One Writer’s Beginnings, “is that which makes up the human memory…the memory is a living thing—it too is in transit” (104).

In Welty’s long short story “Music from Spain,” a pair of memories fuel the action, both of which are influenced by the main character Eugene’s distance (in time) from those memories. One memory is the year-ago death of Eugene’s daughter, Fan. A second, more immediate memory comes in the story’s first paragraph when Eugene, “without the least idea of why he did it…leaned across the table and slapped her {his wife’s} face” (393).

Immediately after this inciting incident, Eugene leaves the house and takes a long walk through the city, eventually accompanied, coincidentally, by the same Spanish musician Eugene and his wife saw perform the night before and with whom Eugene ends up sharing the day. Throughout that day, the slapping of his wife bobs in and out of Eugene’s consciousness, drifting like something on a wave, hiding between the swells one moment, roaring up around him the next. Sometimes the memory is overt. “Why, in the name of all reason, had he struck Emma?” (394) he wonders early in the story. Regularly, he questions himself in this way, his guilt like a slow metronome driving the story. Later, he speaks aloud of the incident to the Spaniard, who literally can’t understand him, “’Chances are’—Eugene had begun speaking again—‘you didn’t know you had it in you—to strike a woman. Did you?’” (414) Later, he’s nakedly accusatory and hostile toward himself, saying “’you know what you did…you assaulted your wife’” (419). These overt remembrances are one way in which memory colors “Music From Spain,” providing emotional and character signposts.

In her memoir, Welty tells us that “writing fiction has developed in me an abiding respect for the unknown in a human lifetime and a sense of where to look for the threads…the strands are all there: to the memory nothing is ever really lost” (90). Elsewhere, Welty calls this ever-present memory the intrusion of “unwelcome realism” (89). One can feel this idea in Eugene’s inability to shake off the memory of what he’s done. Even as he wanders San Francisco, briefly distracted by its colorful wares and wonders, his memory sits heavy upon his shoulders.

And yet, the memories in “Music From Spain” function on a more subtle, elemental level as well. Indeed, the hitting of his wife colors, actually infects, not just Eugene’s conscious mind—what he thinks about—but his subconscious mind as well, intruding on how he sees the world that day. The memory wears the world’s clothing. For instance, the very fact that Eugene is drawn to the Spanish musician is subtly driven by the fact that he and his wife had had a nice time hearing his music the night before. Compounding this sense is the fact that Eugene pulls the musician back moments before he accidentally walks into traffic, literally “rescuing” the positive memory of his music the night before. After this gallant act, Eugene felt “fleet of foot, at the very heels of a secret in the day” (403).

Around him, Emma is everywhere. The memory of having hit her becomes the world he sees, feels, and experiences. Walking along, Eugene sees “In the flyblown window of a bookstore, a dark photograph that looked at first glance like Emma” (397). Then, seeing the fog lift off the city “brought him a longing now like that of vague times in the past…he had suggested to Emma that they take a simple little pleasure trip” (399). A bit later, Eugene and the Spaniard come across a side-show whose central figure is an enormous fat woman named, of all things, Emma. The ticket seller calls into the street all day long, like a belting out from Eugene’s soul, “Have—you—seen—Emma?” (404). Even when Eugene steps forward to look at the poster of the side-show Emma, he perceives a certain look in her photographed eyes. “It was accusation, of course” (405). The photograph of an entirely different Emma bears the stamp of his guilt.

One thinks here of Welty’s declaration that “to the memory nothing is ever really lost.” She projects Eugene’s memory onto the world around him to demonstrate this very fact. Even more subtlety, but lushly, later in the story, Eugene and his companion walk toward the ocean and find themselves at the edge of the city. The Spaniard, suddenly, seems affected by his surroundings and gestures with his arms and body at the city around him, reacting almost musically to his surroundings. Eugene notes that “he was really wonderful, with his arm raised” (414). The gesture of a raised arm here evokes the image of Eugene’s own arm, raised to strike Emma. It’s almost as if Welty is exploring, even playing with, on how many levels she can have Eugene’s memory influence the story.

Compounding the powerful sense that time and distance has on “Music From Spain,” Eugene is not only metaphorically burdened by time, but quite literally as well, for he’s a watch repairman by trade. Welty’s memoir is filled with clocks and watches, with the sense of time and how time affects both life and story. “In our house…” begins her memoir, “we grew up to the striking of clocks” (3). Later she declares that growing up around clocks, and with a father that tended them, taught her the value of chronology. “It was one of a good many things I learned without knowing it; it would be there when I needed it” (3). Eugene’s profession creates not only a subtle deepening of Eugene’s character, but perhaps a small private wink to Welty’s own life as well. In “Music From Spain,” time is a broader, though no less important factor, than memory. In fact, as the story progresses, we feel that the immediate memory, that of Eugene having hit Emma, though more in focus, is in actuality dwarfed by the more haunting, less resolved memory of the death of Eugene’s and Emma’s daughter, Fan. In this way, time weights heavy on the story.

One senses that, regarding moving on from Fan’s death, Emma’s burden is greater than her husband’s. In the moment in the story when Eugene sees the fog lift and is reminded of having suggested to Emma that they take a trip to see the world, we learn that “it had been his luck to mention it on the anniversary of Fan’s death and she had slammed the door in his face” (399). The revelation that the “time” of Fan’s death has grown soft enough to Eugene that he likely doesn’t remember the exact day, where Emma remembers all too well, speaks to the contrast in their abilities to cope. Eugene’s memories of Fan seem sweet and fond, but Emma’s, at least to Eugene’s eyes, are darker and more complex. We learn that Emma has grown heavy with age. He refers to her at one point as “a fat thing” (395). But, regarding that extra flesh on her body, “she said it had only been there since the birth…she blamed little Fan with it. Out of the middle of her grief she could rise and put her unanswerable pink finger on Woman’s Sacrifice” (413). Later, Eugene and the Spaniard arrive at the beach. Eugene remembers a time when he and Emma had picnicked in that very spot and been unburdened by the tragedy. “Where was little Fan then? That hadn’t bothered them that day” (418). And yet, the separation remains. For in that same scene, Eugene notes “the deepening sky was divided in half as it often was at this hour, by a kind of spinal cloud” (419). This image of division, of two sides of something, metaphorically deepens the divide between Eugene and Emma, and offers further evidence of why he might have struck her, an act for which he never quite atones or comes to grips with in the story.

Another way Welty approaches time is through how it’s divided and experienced within a story. “Greater than scene, I came to see, is situation” (90) writes Welty in One Writer’s Beginnings. That sense is all throughout “Music From Spain” and affects the passage of lived time. True, there are distinct scenes: the moment he slaps his wife, at the restaurant with the Spaniard, at the beach, back at home at story’s end. But the story is not “scene driven” as much as it is driven by situation and circumstance, the situation of a man coping mentally with a pair of heavy and immovable memories which have affected, and doubtless, will affect his relationship with his wife, whose love has become strained and changed by the death of their daughter. This commitment to situation allows Welty to drift through time rather than simply walk through it. It gives her the freedom for the story to unfold gradually. And indeed, though the story has chronology, its usage of time feels like an invented logic rather than the simple passage between beginning and end.

I’m reminded here of a revelation Welty speaks of in One Writer’s Beginnings. In referencing an early story, Welty writes, “writing ‘Death of a Traveling Salesman’ opened my eyes. And I had received a shock of having touched, for the first time, on my real subject: human relationships” (87). For of course “Music from Spain” is, at heart, a story about relationships. But by choosing to keep the story tightly in Eugene’s point of view, the choice to not hear directly from Emma on these two memories, is profound in our experiencing of them and in how they’re remembered. For certainly Emma would have a different take on her own daughter’s death, and on having been hit, for the first time, by her husband. So, then, “Music From Spain” is not just about Emma and Eugene, but also about Eugene and Eugene. It’s intrapersonal, perhaps, even more than it’s interpersonal. This is re-enforced in the narrative distance, as well as the language barrier, between the protagonist and the other main character, the eccentric Spanish musician, who seems in the end to be present more as foil, as mirror, for Eugene, than as a full functioning contributor to the action at hand. How the events are experienced and remembered—again, time and memory—are explored not just through memories and images, but through narrative space as well. It’s a marvel the many ways Welty is able to explore these concepts, imbuing every facet of her story with their logic.