Theodore

Theodore Gabriel Watson awoke early on the day he was to unintentionally kill a fifteen-year-old white girl, feeling like a diseased mouse had crawled inside his mouth during the long cold night and died there. He was staying in a rooming house down by the heavily-polluted though still regularly-fished Jackson River. There were eleven damp and dimly lit rooms for rent in the large ugly house by the smelly river, but only two were presently occupied, his and another on the floor directly above his. The other occupant was an elderly silver-haired Russian fisherman named Luka. The boat Luka worked on had suffered a mechanical glitch when it last docked, and due to a poor sense of time and geographical awareness, Luka was left behind when the boat set sail three days later. Now he was stuck in a foreign land with little money and barely a word of English to his all but unpronounceable surname.

Theodore twice tried to befriend Luka at the behest of their Hungarian landlady, Marta (who also spoke little English, and who Theodore believed, had a “thing” for the old Russian fisherman), but had gotten nowhere. Luka would merely look to some distant point directly behind and off to one side of Theodore whenever the young man spoke; the old fisherman nodding his great silver head and pulling at his long silver beard in response to this unassuming man prattling on at him with his utterly incomprehensible words.

Theodore was thin and black and quite short, with big protruding bright eyes and large misaligned teeth. He spent much of his conscious time skulking the city streets in varying degrees of physical and mental anguish, nodding at people he perceived to be nice, shunning those he thought to be a threat. In his youth he had constantly fallen afoul of white and black bullies alike, had screamed “nigger fucker!” while being beaten to the ground by an unemployed white dockworker, had thrice called a black antagonist (a repeat offender Theodore could rarely seem to avoid), “Winston cocksuck fucking Churchill!” as the heavy and nonplussed youth of similar color struck Theodore about the head and buttocks with a length of garden hose he carried at all times looped through his canvas belt.

Theodore was running on a streak of bad luck of late, and he was running fast, with his head down and his eyes shut tight. His mother had died a few months ago (which Theodore viewed as the best of the bad luck), leaving her only child the sole beneficiary of her entire wealth, which after tax, burial costs, and the settling of many overdue bills, amounted to: $1024.23. Theodore went about spending this relatively paltry sum (a king’s ransom to Theodore at the time) with an insane alacrity. He bought a four hundred dollar engagement ring for a girl he had dated only twice but wrote to over a dozen times. She willingly took the ring with a wry smile then told Theodore to never call her again. When Theodore took her firmly by the left elbow and pressed his heartfelt case to claim what he thought was rightfully his for the taking (namely her unbridled love and lifelong commitment), her ex-high school linebacker and current chalk-white troglodyte beau, Daryl “the bull” Carlson, stepped out from behind a rhododendron bush beside the girl’s house and knocked out two of Theodore’s teeth and kicked him so hard in the balls Theodore doubled up and nosily shit himself right there in front of them both.

Theodore then spent sixty dollars on self-help and martial arts home-training books. He left the self-help books on a bus one rainy afternoon and used the martial arts books for toilet paper and doodling aids during one particularly lean and boring week. The rest of the money went for booze, drugs, and into the purse of Luscious Ling-a-Ding, an obese fifty-three year old Hawaiian whore who worked the springs of an aging bed in a tiny room above the pet store.

For three sultry sex-infused and groin burning nights, Theodore thought himself in love with Luscious Ling. She was magnanimous in both size and carnal proficiency, and when her tremendous thighs gripped Theodore’s flappy ears like a cushioned vice made for trapping Alaskan caribou with care, he thought himself to be on the joyous and agonizing cusp of heated heaven and pungent hell, where only much diligent licking and an ability to breathe in rapid shallow gasps, would ever set him free again.

When the money ran out Luscious Ling’s door and thighs closed with equal finality above the mewing of kittens and the squawking of colorful birds. Theodore went back to his rented room and wrote his love reams of awful poetry, pages of stagnant prose, tomes of utter banality; which of course, Luscious never read a single word of.

On the day he was to mistakenly cause the death of a young white girl, Theodore sat on the edge of his sagging bed and held his long face in his hands. He could hear Luka grunting and groaning in the restroom at the end of the hall. The waft of the Russian’s hard earned efforts mixed with the acrid smell of Marta’s intensely strong coffee, the damp of the room, and the cloying stench from the nearby Jacobson’s Processing Plant, made Theodore’s stomach turn. He slowly stood and stretched, flinching at the flare of pain along his back and across the thin band of his shoulders. He scratched his groin and went over to the window and looked out on the rusty corrugated siding of the old processing plant that stood directly across from the east side of Marta’s chilly building.

Once a week Theodore would apply for work at the plant, knowing he could never lift the heavy slabs of beef or pork, nor last longer than a few hours standing in all that reeking wet heat and deafening noise. The HR staff at JPP seemed to know it too; they looked at Theodore as he stood before them each week with his application form in hand as though he were some ill-defined threat formed in the darkest reaches of their guilty Caucasian minds. Theodore had no way of knowing what they thought of him and did not care, just as long as they kept rejecting him for work (citing reasons readily given by Theodore himself: an inability to lift anything close to seventy pounds, an inability to stand for long stretches of time, an inability to operate heavy machinery, an inability to work under pressure with great speed and dexterity. etc) which in turn kept his unemployment checks coming with almost clockwork regularity.

Finally the sound of the toilet being flushed twice came from the end of the hall and Theodore waited the requisite ten minutes before going in to relieve himself. He washed his hands and then went downstairs to the dining area. This was the largest room in the house, and possibly the bleakest. Four plastic tables covered with paper tablecloths and surrounded by chairs of cheap and dissimilar design were spaced out on the threadbare carpet. Thick dusty curtains remained drawn across the three large windows that looked out onto Harbor Street, for the morning light irritated Marta and could easily trigger one of her frequent and disabling migraines. The huge archaic fireplace was the centerpiece to the room, standing dark and empty like the entrance to a Tolkien cave. Marta rarely forked out extra money for firewood and when roomers unaware of this fact complained about the damp and cold she would draw them an indecipherable map to another place nearby owned by a homosexual couple from Sweden; a place that was warm and clean and charged six times Marta’s rate. The complaining roomers (most of whom were alcoholic itinerant fruit pickers or alcoholic fishermen or alcoholic meat workers from JPP) would don their wool knit caps and fingerless gloves and go back to the serious task of drinking and saving themselves a few dollars by staying put.

Marta was sitting at one of the tables, drinking coffee and smoking one of her five-a-day only expensive European cigarettes. Luka was filling a large china mug with Marta’s strong coffee from the urn. He nodded at Theodore. Theodore nodded back and gave a little wave to Marta. She smiled from behind a blue haze of acrid smoke. This had been the ritual since Theodore moved in six weeks ago. Silent nods, bitter smoke, strong coffee, and a large cold room with barely a hint of natural light.

Theodore poured himself a cup of coffee and sat at Luka’s table. He had been meaning to ask Luka if there were any black people living in Russia. Theodore considered for a minute how best to frame this question so the old man could understand, when it suddenly occurred to him he really had no interest in the matter at all. There could be five million blacks living in Russia or only one. Either way it would mean nothing to Theodore. So instead he just sat himself across from the old fisherman and smiled. The old Russian smiled back at the young black man and the second part of the ritual began.

Marta went to the kitchen and returned with two large plates, each piled high with thick slices of buttered white bread, cooked runny eggs and chunks of grey odd-smelling meat. It was the same every day, one meal a day, six days a week, with nothing offered on Sundays, Marta’s day of rest and reverie.

The men ate in silence and Marta went back to her table and cigarette, and the silence prevailed. Halfway through the bland meal Theodore caught the old Russian and the old landlady eyeing each other across the gloomy space and he knew then with certainty that something was going on. He would soon leave like he did each morning, to roam the streets and lose himself in a maze of thought, and he imagined the old couple quickly coming together the moment he left, their coarse claw-like hands moving like stony spiders beneath the thick layers of clothing, their dry lips mashing together like the closing of an old leather wallet. He loathed to think more about it and set about finishing his greasy meal in a hurry.

The day Theodore was to mistakenly kill a girl was a particularly cold one. Dark clouds bullied the sun and bitter winds ran amok through the narrow streets. Theodore walked briskly along with his thin arms folded at his chest and his large woolen cap pulled tightly about his ears. He belched and his cheeks inflated with the sickly warm aftertaste of runny eggs. He was light-headed from the strong coffee and his bowels had started their regular mid-morning churning as Marta’s fare began working its way through him. He had nothing in mind to do for the day. His unemployment check was late and he was down to his last dollar and change. As he walked he thought about his mother’s small one-bedroom home, which he believed by rights should have been his, but had been reclaimed as a foreclosure by the bank and quickly sold again. He could have settled in that house nicely, he thought, done away with all his mother’s garishness and started over.

Theodore Gabriel Watson was not a particularly sad young man, nor was he an angry one, but he was aware that his life lacked direction and purpose. He thought about the little involvement he seemed to have in the direction his life was taking, and he thought about how and when this could change. The principals that governed his life were not the traditional ones built on the notion of hard work and ambition, but rather ones of reclusive inactivity and a misplaced sense of entitlement. In time something good was bound to come his way. He figured all he had to do was keep himself aware and receptive to the possibility.

He walked like this for a while, his mind wrapped around such thoughts, his thin arms wrapped around his body, the wind assaulting any exposed portion of smooth dark flesh it could find. This was the way it had been for the last several days, unless it was raining or snowing: a young impoverished man of simple means out in plodding pursuit of nebulous wants.

He passed by the pet store and instinctively looked up and felt a remorseful twinge in his chest. Luscious Ling. He could have loved her well. He took a left on Hillrise and began trudging downhill toward the river. He fingered the dollar and change in his pocket and thought about getting himself a drink. Sammy at the liquor store might let him have one of the warm bottles of Bud that he kept in the back for a buck, but that was way over in the other direction and Theodore was already halfway down Hillrise now and the river was there, just ahead of him, rippled grey and odorous, carrying along its omnipresent chunks of flotsam.

He first saw the girl as he crossed Shoreline Lane and began moving beside the massive blocks of jagged stone and concrete that were set there sixty years prior to help keep the river and town divided. She was sitting on a large painted block of concrete close to the water’s edge, her knees drawn up beneath her chin, her arms wrapped about her shins. She wore a large floppy dark green hat and a bright red scarf that the wind longed for. Theodore would have walked on by had the young girl not turned to him and waved. He stopped and waved back. Then there followed a moment of quiet stillness between them.

A large seabird alighted on the water, flapped its wings a few times, then folded them against its sleek body. It bobbed along on the choppy current and began pecking here and there among the surface trash. The girl smiled at Theodore and beckoned him over. Theodore smiled back. There was then just the slightest hesitation on his part, some barely perceived jolt of unease turning within him. He looked back behind him, back toward the slow lazy motion of a small riverside town going about its midmorning business on a cold autumn day. Had he seen just one thing to draw him from this time and place, just one commonplace action or everyday dull event to keep him moving: the slamming of a car door, the turning over of a tired engine, the calling out of another voice, the striking of the town’s clock tower as a new hour began, even the flap of a single sheet of paper snatched by the wind and set on a maddening and undisclosed course. All or any of these tiny happenings could possibly have adverted things, kept the balance in check, kept two hearts beating and a single mind safe from the claims of utter despair. But Theodore saw no such thing to give him pause (nor did he know he was looking for it), and when he turned back to look again at the strange girl with the downcast smile sitting by the polluted river, she was already up and moving his way.

Her name was Faye and she was alone. Fifteen years old or so she said. This was her first day here. She had slept the previous night in the frigid hulk of a rusted out Chevy lodged between similarly massive stones some miles downriver. Theodore knew the car she spoke of, had sat in it once himself, with a glass pipe to his lips and his mind twisted like forked spaghetti.

She asked for a cigarette and when Theodore told her he did not smoke, she asked if he drank. The clouds darkened and swallowed up most of the morning sun’s unsatisfying yield. She was a poet, she told him. She had had it rough, had walked away from her previous life unloved and unchallenged and without regret. She saw no sense in returning. They sat together and talked, or rather, she talked and Theodore listened. She said she would like to find a commercial fishing boat and maybe work her way to another country, although she didn’t have a passport and had never been to sea. Theodore thought of Luka, saw the old man’s face nodding in bewilderment as he was told the tale of Faye. Maybe she could travel with him, back to wherever the hell it was the old man came from.

When it began to rain they got up and moved carefully across the stones, turning their feet inward for grip on the steep slopes, their arms spread apart like ridiculous wings for balance. Without money they scuffed their heels and kept their hands in shallow pockets or in the warming depths of their armpits, walking aimlessly here and there like abandoned acolytes. They bumped against each other as they moved, Faye talking now and then in windswept muffled tones, her pointed chin rubbing against the collar of her thin shirt. Theodore listened and nodded, but heard little of what was said. She was pretty and needful and that alone kept him going. He seemed to care and want to know and that kept her beside him.

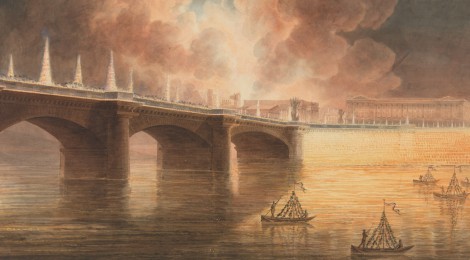

Without a place to go that would not demand money, they walked and walked and soon found themselves crossing Jefferson Bridge, where the rain rushed toward them at a piercing sideways angle and the grey clouds seemed to thicken. Midpoint across the bridge they stopped and looked at the jagged rocks and the dirty river some sixty feet below. They talked of drugs and of local availability. Theodore thought again of his mother’s house, now gone beyond his reach and of how if things were different, he could have taken Faye there, offered her some comfort, a safe place to collect her thoughts, a warm bath, her pretty face clean and smiling with genuine gratitude. He could try again at JPP, he thought, this time with heartfelt intention. He could flex his small biceps and shake off his dour disposition. He could tell them a change had come about and he was much more willing now, for he had purpose. Faye brushed by him and stood against the railing. Theodore felt a rare sense of tranquility, amazed at what little it took. Just simple contact with another human being, another lost soul.

With her hands placed on the cold dark steel, Faye easily pushed herself up and stood on the narrow beam. She was once a gymnast, she told him, had won herself a bevy of cheaply-made trophies and brightly-colored polyester ribbons. They were all in a box someplace, collecting dust and darkness. Her achievements meant nothing to her family, much like her leaving. Theodore looked at the space behind Faye, the air now distorted by the miserable weather, buildings far in the distance seemed to ripple and unfix themselves like sheets of fabric. Birds in flight fought to gain every haphazard yard of space, only to quickly lose it again. Faye turned on the toes of one foot; her arms stretched wide like outriggers on a fishing vessel, one bound for Russia perhaps. She smiled at Theodore and turned, and in a blind panic at what he was now actually seeing, he rushed toward her, his heart clawing the walls of his chest in terror, hating himself for idly standing by, for not taking action as this girl took such a ridiculous risk, hating himself for being him.

Faye on the other hand was perfectly at peace, her eyes momentarily closed, the cold wet air lifted her hair, billowed out her puffy hat, teased her scarf out into the void behind her, a yard of bright red rippling like blood on the surface of a clear stream. Theodore had never felt such fear as he scuttled awkwardly over the slick surface of the bridge and reached for her, his small hand stretched out with the fingers set painfully wide apart, like the comical hand of a clown. He could see a small tear in the front of her jeans, just below the left knee, the ragged strands of white there whipped by the wind, a tiny window onto the pale young flesh behind the denim.

She opened her eyes just as Theodore reached her, a quizzical look washed over her, her arms began drifting back down to her sides, she turned herself slightly, she wasn’t afraid, she had done this a dozen times since leaving home, she had always been a climber, “our little monkey,” her mother used to call her, before she stopped calling her anything at all. As Faye smiled and reached for the upright beam beside her, something she could hold onto as she turned herself and scaled back down to where this funny looking man was, Theodore’s arm shot through the gap between her ankles like a lance, his aching hand closed on wet air, his shoulder connected hard with her shin, momentarily covering the tear in her jeans and knocking her from the bridge and out into the cold wind’s irrefutable grip.

She made not one sound as she fell, and though he could not have heard it because of the fury of wind and rain and of his own pitiful howl, Theodore felt the impact rip into him like a savage bite, and he fell too, to his knees, then to his side, where a small puddle of water churned near his broken face and darkness took his mind.

In time he stood again, held together by he knew not what, and when the railing pressed into the hollow of his stomach, he stopped and looked down and saw her there, spread like the bright center of a flower with petals of steel grey. He looked for other people and there were none. He was alone, she was alone, though they would now always be together. He willed himself to move and did so, his hand trailing along the wet surface of the railing but not feeling it. And as he walked images came to mind, the faces of the day and others from years before, all moving around the countenance of Faye at the center, like a Drew Struzan movie poster depicting a dark and tragic tale.

Many hours later, after the weather had run its vicious course and the clouds once more gave the sun its due, an elderly jogger crossed the bridge and stopped for a breather and to admire the view, and looking down, he saw a young black man nestled in the crevice of two great grey stones with a young white girl held across his lap, her arms spread wide, her head back at an awkward angle, with the now much milder wind gently teasing her long hair. The young black man was rocking back and forth and the young white girl rocked with him and the jogger thought the position somewhat strange and surely a bit uncomfortable. He shook his head and smiled, the youth of today, he thought, and moving on again into a slow and steady lope, he thought back to the days a half century before when he and the woman who became his wife first started dating, how they too could sit by the river like that, wrapped about each other, entirely lost in love, no doubt looking just as strange in their time.