Patrick Geddes: The Father of Modern Town Planning

Called the “father of modern town planning,” Patrick Geddes (1854-1932) was a Scottish academic based in Edinburgh, and the author of Cities in Evolution. As Pierre Clavel writes in his introduction to a 1971 reprint, Geddes:

began as a biologist, spent a fruitful but largely unreported middle period as a university and civic reformer, and then began, in his 50s and 60s, a highly visible and international public life with an increasing focus on city planning.

He read and traveled widely, promoted his original ideas through speeches and exhibitions, wrote reports and drew plans for cities in Scotland and India, drew a master plan for Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and planned the new city of Tel Aviv, beside the ancient port of Jaffa.

Geddes was ahead of his time on issues such as ecology, preservation—both of green space and of historic structures—and the involvement of citizens in the planning process. The title of his book Cities in Evolution makes a clear link between the fields of biology and urbanism. Versed in sociology, he brought its new methods of scientific research to bear on questions of urban form, expansion, interior structure, change over time, ethnic makeup, income distribution, and seemingly every other aspect of cities. He saw that in the modern age we all must live in cities, so he advocated making our cities good places to live.

This year marks the centennial of Cities in Evolution, published in London in 1915. Subtitled “An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Cities,” the book is not well known today. A 2012 reprint in paperback is available, significantly from Forgotten Books. So far as I know, no plans are afoot to celebrate the book or the man. Two biographies exist: Patrick Geddes: Maker of the Future, by Philip Boardman (1944) and Pioneer of Sociology: The Life and Letters of Patrick Geddes, by Philip Mairet (1957). A footnoted edition of Cities in Evolution, with better illustrations, would be welcome.

Geddes had a strong influence on Lewis Mumford, the American writer on cities and city planning, and Mumford in turn had a profound effect in the United States, especially through his book The City in History, published in 1961. I have a vivid memory of discovering The City in History around 1968 in my high school library. Along with books on ancient civilizations and a copy of Vitruvius, Mumford’s monumental book eventually led me to become an architect.

Reading Geddes produces an eerie sensation, as he forecasts much of the century to come. Every city and town in the developed world, for example, now has a department of planning staffed by professionally trained engineers and designers. And these have at their disposal a wealth of maps, surveys, photographs, charts and reports, to show existing conditions and to use as a base for projected improvements. Geddes campaigned for collecting this sort of data. He called it a “civic survey,” a phrase which is apt to mislead, as it includes much more than land surveying. For Geddes, a survey should include the condition of buildings, notes of historical and artistic value, and a description of the inhabitants.

Housing, Geddes felt, forms the most important component of the city—not boulevards, public squares or great buildings. Since the wealthy can provide for themselves, he stressed the need for laws and subsidies to provide decent housing for the middle and working classes. Good housing implies good neighborhoods, and he recognized the importance of mass transit, parks, recreation, local centers, and safe places for children to play and grow. Using a kind of shorthand, he called this idea “health.”

In northwestern England, in the industrial belt built over coalbeds and called the Black Country, the evils of air and water pollution, low wages, overcrowding, and a stunted urban landscape were obvious. Yet industrial Glasgow, Geddes said, was the most progressive city in Britain. He discusses the merits and defects of Paris as rebuilt in 1853-1870 by Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann. He admires new developments in Germany, and one chapter describes a junket of British professionals to Cologne and the Rhineland. His praise for German ideas, river ports, and city staff is all the more remarkable in the climate of the World War. Geddes ridicules the journalistic hysteria of the time, and he seems to dismiss national politics.

If Geddes has a blind spot, this would be it. Yet he certainly met political roadblocks, and he exploited his connections to high officials in the British government. They provided his entrée to India and Palestine. In Scotland, his promotion of public meetings, citizen participation, and museum exhibitions on city planning can be interpreted as an attempt to outflank entrenched politicians and their wealthy business allies. Rather enigmatically, he lumps these public activities under the word “civics.”

Education and publicity are key parts of his vision for urban improvement. He also touts the “civic pageant,” a reenactment of the city’s history, or “the more interpretive masque of a city’s life.” He staged such pageants in Scotland and India, and they had a vogue in the United States through the 1950s, often to mark a significant anniversary. Today, the costumes and speeches find an echo in the “interpreters” at historic sites, and in recreations of historical events on film. But a street-theater presentation of the Dutch foundation of New York, let’s say, would be strange today—and perhaps wonderful.

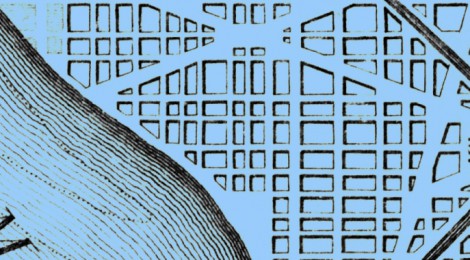

In design, Geddes condemned the “gridiron” plan of straight streets, rectangular blocks and endless replication. The grid, as we generally call it today, fails to use or actually destroys natural features like hills and streams; it stamps the landscape like a machine. The plan of Tel Aviv, with its curving streets and sensitivity to contours, shows what Geddes prefers. But a grid can be adapted to any situation, and it has the cognitive benefit of orienting the resident and especially the visitor. Along with Frederick Law Olmsted and other late-nineteenth century designers, Geddes may have elevated an aesthetic preference to a principle.

A man of action as well as of words, Geddes bought and renovated a group of slum houses in Edinburgh. He did the same with a five-story building in the High Street to house a permanent exhibition on urbanism. With a rooftop terrace, a belvedere, and a panorama of the region, the Outlook Tower is still there, a tourist attraction near Edinburgh Castle. The book includes a drawing, calls the Outlook Tower a “civic observatory and laboratory,” describes it in detail, and recommends it as a model for other cities.

Very much related to politics is Geddes’s concept of the region. A city that cannot look and act beyond its legal boundary lines is doomed, and planning which stops at those lines will literally fall short. He considers the region of Glasgow, Edinburgh and their shared valley to be one urban unit, and Liverpool-Manchester to be another. London and Berlin, he notes with approval, annexed huge areas of land, and they swallowed villages whole. In the United States, he sees that the coastal cities of the northeast are growing together, from Boston to Washington, DC. For all these, he coins the word “conurbation.”

Geddes seems to foresee the vast scale of Tokyo, Delhi and Mexico City, cities with more than 20 million inhabitants. He notes the peculiar status of a city like New York, an economic powerhouse but not a political capital. Above all, he says that each city has a unique set of geographical and social facts to work with. No planning model or theory is adequate to deal with such information. In this regard, he is the opposite of Le Corbusier and his American followers, whose “sweeping clearances” for superhighways, superblocks, and high-rise low-rent towers proved to be a disaster. “Conservative surgery” with infill construction was the right approach, as Jane Jacobs would echo fifty years later.

Geddes coined two more words which have resonated, “paleotechnic” and “neotechnic.” The first refers to what we call the first Industrial Revolution, a phase of large factories, steam power, coal and steel production, and railroads. Already in 1915, there were signs of a new era of decentralized manufacturing, electricity, and air travel, the neotechnic. He extols hydroelectric power, developed in Norway, as “white coal,” and he assumes that scientific progress will continue. Thermonuclear power, computers, digital technology, and the emerging business of bioengineering show that he was right. He predicts “new and appropriate forms of finance,” such as cooperative lending, beyond the banker who is “sunk in the cult of personal gain.” Here, he may have been overoptimistic about greed.

In 1924 at the age of 70, Geddes moved to southern France. In Montpellier, he established a school called the Collège des Écossais, which looked and functioned much like the Outlook Tower in Edinburgh. According to Pierre Clavel, “as he grew older, he became less willing to listen, more insistent on spreading his ideas through various schemes and promotions.” Mumford noted that Geddes wanted “disciples,” followers instead of colleagues.

His influence went beyond ideas, though. Mumford’s remarkable prose style owes something to Geddes, who must have drawn from his public speaking when he wrote. By all accounts, he was a charismatic and energetic figure. He apparently saw himself as Celtic, which is to say inspired. In Cities in Evolution, he slips at times into a kind of poetry, allusive and metaphorical, and the sense is lost. At the end of Chapter V, “Ways to the Neotechnic City,” he writes:

As I close this chapter I see from the morning’s paper how the archons of a sea-coast city, having in past years built a gymnasium to Apollo, and likewise a temple to Hygeia, whereby their youth are blest, have now also offered a modest sacrifice to Poseidon. This the good sea-god . . . rewarded with the miracle of an unfailing spring of sea-water upon their acropolis.

The abstract that heads the chapter ends with the cryptic phrase: “Poseidon at Dunfermline.” Dunfermline is a town in Fife, Scotland. The gymnasium is clear enough, but the rest of the Grecian imagery remains obscure. Still, in an age when few academics write with color or even clarity, Geddes is a brisk northerly breeze.